Marcos, Sotto Zero In on Alleged Flood Control Anomalies

President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. and Pasig City Mayor Vico Sotto have both issued sharp public rebukes over alleged anomalies in flood control contracts —citing collusion, substandard work, and questionable bidding practices.

On Monday, August 11, 2025, Marcos doubled down on concerns he first aired in his July 28, 2025 State of the Nation Address, where he called out erring contractors:

“Mahiya naman kayo sa inyong kapwa Pilipino… Mahiya naman kayo sa mga anak natin.”

The President said his administration had already identified companies whose work was “obviously subpar.”

“We already have some names… We will put them on a blacklist. Hindi na sila puwedeng mag-kontrata sa gobyerno. ‘Pag hindi sila makapag-explain nang mabuti, we will have to take it to the next step,” the President warned.

In his SONA, Marcos was more blunt: “We clearly saw for ourselves that many flood control projects were failures —they crumbled, and then, there were others existing just in the imagination.” He accused corrupt actors of hiding behind familiar schemes: “Let us not pretend anymore… The public knows there are rackets behind these projects… kickbacks, initiative, errata, SOP, ‘for the boys.’”

Figures from the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) show that 15 contractors accounted for roughly 20% of the P545-billion flood control budget from 2022 to 2025—about P109 billion.

Six Stages of Corruption by Vico Sotto

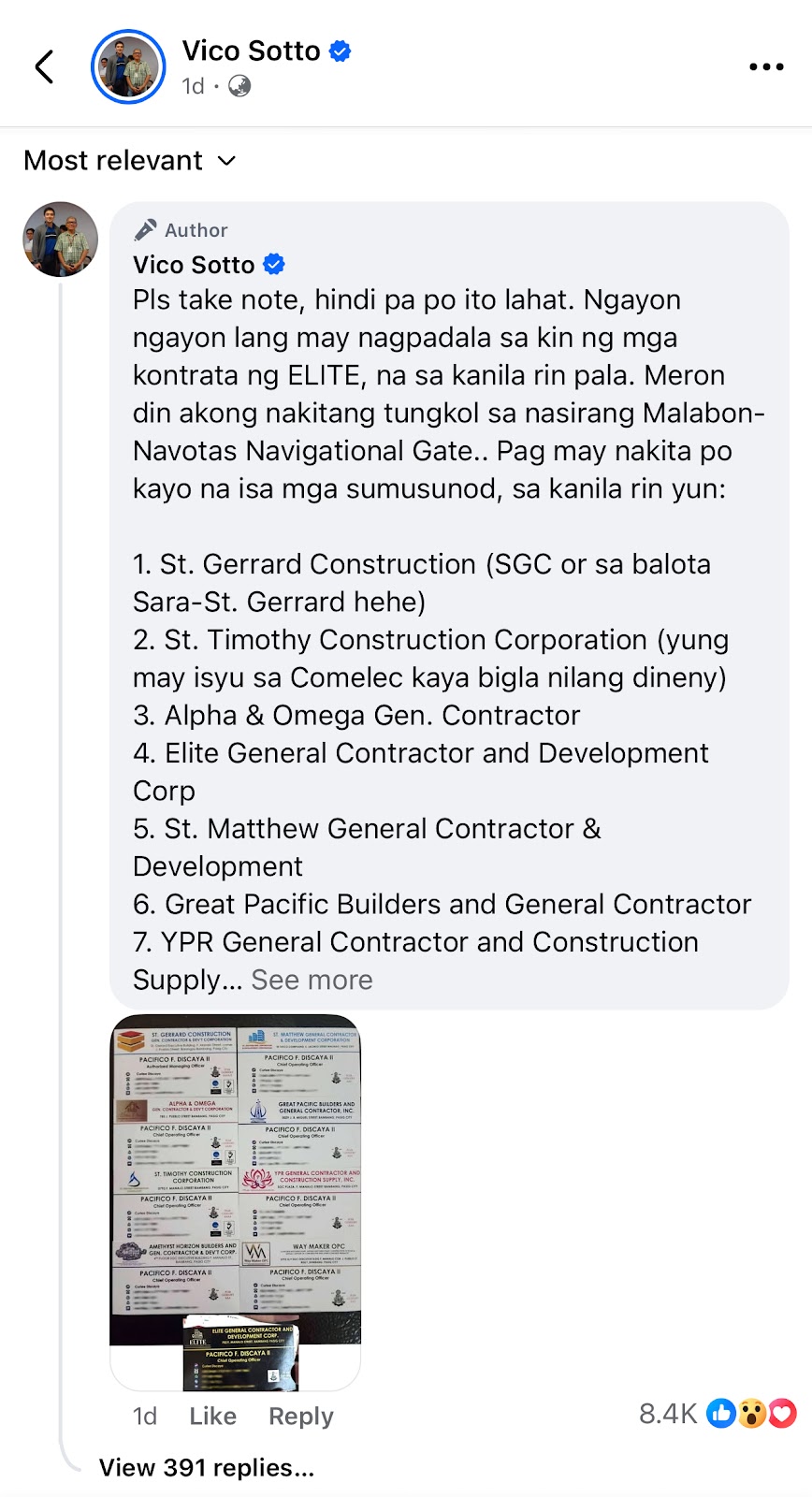

Earlier that day, Sotto took to Facebook to outline what he called the “six stages of corruption,” a pattern he says is widely recognized in government, from collusion during bidding to substandard or ‘imaginary’ implementation, inflated costs, tax evasion, and, eventually, using illicit gains to fund political campaigns.

He alleged that Alpha & Omega and St. Timothy—both appearing in the DPWH’s Top 15 contractors list—along with other firms that the Pasig mayor said to be “owned and controlled by the Discayas.” These ownership claims have not yet been independently verified.

Sotto further alleged that some top contractors declared zero gross revenue to the local government despite winning multi-million peso projects. The Pasig LGU is now pursuing tax collection cases, which he said could fund major civic infrastructure without cutting other programs.

Where There Is Flood, Money Bleeds

Flood control has long been one of the DPWH’s biggest spending areas amounting to nearly P1 trillion from 2023 to 2025. Its technical complexity, geographic spread, and urgency in the face of climate-related disasters make it susceptible to procurement shortcuts and weak oversight. Past Commission on Audit reports have flagged incomplete, delayed, or substandard works in this sector.

What’s Being Done

Following the release of the Top 15 list, Marcos ordered the DPWH to audit all flood control projects since 2022, with blacklisting possible under RA 9184. Confirmed anomalies will be referred to the Ombudsman for prosecution. A Palace spokesperson emphasized:

“Even if it’s close to the heart, even if it’s a friend, the President will not spare anyone. Those who should be held accountable will be held accountable.”

In Congress, a House tri-committee has begun hearings on contract awards and corporate ownership. The Senate is preparing to subpoena corporate records from the SEC to verify alleged links between contractors and political networks.

At the local level, Sotto said Pasig City will forward its findings to the President and continue its legal cases to recover unpaid business taxes.

Marcos’ naming of contractors and Sotto’s direct allegations mark a rare, coordinated spotlight on infrastructure anomalies. But moving from exposure to resolution has historically been slow: blacklisting requires airtight proof; corporate structures can obscure accountability; and political resistance can mount as cases advance.

Still, by placing both figures and allegations on public record, national and local leaders have invited citizen oversight. Sustained pressure—paired with verifiable audits and legal follow-through—could determine whether this becomes another stalled reform drive or a genuine break from entrenched practices.

.svg)

.svg) SHARE TO FACEBOOK

SHARE TO FACEBOOK SHARE TO TWITTER/X

SHARE TO TWITTER/X SHARE TO LINKEDIN

SHARE TO LINKEDIN SEND TO MAIL

SEND TO MAIL

.svg)

.svg)